About Ghosts of Our Former Selves - chapter 4 (voice lessons)

Chapters 1, 2, and 3 start the story and each is short. If you have the time, please start there.

About the inspiration for the album, Ghosts of Our Former Selves

Chapter 4 - Voice Lessons

I was reminded suddenly one morning that, until the advent of sound recording, each generation would carry the voices of the previous generation in memory and when they died, those voices would be lost forever. Even though we can now record voices to share in the future, I think that this history of impermanence is part of what invests our sonic memories with such special power. That feeling of imminent loss remains and is yet another reminder of our own mortality.

The voices of so many people I have known, including the composers I studied with, all still live in my memory remarkably intact. I can recall the details of only a few lessons, but there are sentences that stick in my memory and I hear each one in the voice that spoke it. Mario Davidovsky was my teacher the longest, and became a dear friend. Anyone who knew Mario will tell you that his voice, like his music, was full of character. In spite of decades living in the US, he never lost that wonderful, musical Argentine accent. I can still hear the sound and the rhythm of each of my teachers’ voices vividly: Elliott Schwartz, Tom McKinley, George Edwards, and Jack Beeson. And there is a long list of other interesting voices, including Milton Babbitt, Bebe Barron, Elliott Carter, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, Don Martino, and Ralph Shapey, each memorable in its own way.

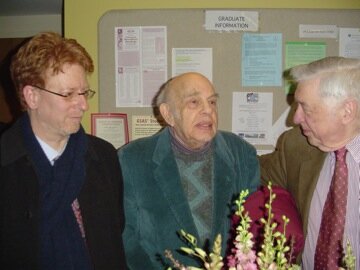

Mario, Elaine, Eric, Simon, NYC 2008

Composers Bebe Barron and Judy Klein at SEAMUS 1998

There are many historical musical precedents that focus our attention on details of the sound of the human voice. Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge and Berio’s Omaggio a Joyce, from the 1950’s, provided new landmarks. Davidovsky used to say that Berio had used up the opportunity and that since 1958 every piece that used spoken word just sounded like Omaggio a Joyce. This is one point on which he and I disagreed. I find that there are nearly as many different possibilities as there are voices. And if you add the meaning one can create through the interplay of text with the sounds of voices, the opportunities are endless. My interest in those opportunities really accelerated in the 1990’s when my wife, Barbara, and I started our oral history project, the Video Archive of Electroacoustic Music, capturing the first-person stories of some of the pioneering engineers and composers. As I began to edit those interviews, hearing the details of each voice over and over, an abstract music emerged from the timbres and rhythms. I started to hear some of the interesting phrasings as part of a musical counterpoint. After that, it was inevitable that I would start to turn these characteristics into new pieces of music. The act of composing with this material, I realized, was my composer’s way of “reading” the stories and was creating part of the scholarship derived from the archive.

My exploration of the power of the voice in electroacoustic music has been evolving since at least 1996, actually just prior to starting the archive. I then began a series of composer-portrait pieces using a combination of recorded voices, some from our archive, together with my reflections on the music of each subject. The first was a tribute to Milton Babbitt (one of the pieces that I wrote about in the 2005 journal article, COMPOSING FROM MEMORY: the convergence of archive creation and electroacoustic composition.) Next, I reached back into my Beatles obsession to make a piece about John Lennon and after that turned to Mario (for his 70th birthday), then to a commission for the Stefan Wolpe centennial. Two big pieces centering on the voice came around the turn of the millennium. Crossing Boundaries (a commission from Bates College) incorporates a dozen voices – composers, actors, family members and friends, all abstracted into archetypes. Dream Songs, for orchestra and tape is based on layered sung and spoken recordings of John Berryman’s poems, taking advantage of the ever-shifting range of attitudes and characterizations in those texts.

The fifth song of Ghosts is all about that moment of clarity I had, with all these voices, “fly(ing) in my head.” I am writing about the voices now, however, not just to describe my artistic practice, but also to see if I can recall some of my more transformational experiences with people who have been so important to my journey.

I met Elliott Schwartz and had my first actual composition lesson sometime in 1973 or 74. The lessons were ear opening. My first assignment was to write the “same” piece three different ways; once using only words to describe what would happen, a second that would be whatever I thought 12-tone music was (I really didn’t know), and a third in which I was free to do anything I wished. For someone who had always thought in the notes and most often harmonically, it was a strange and revealing experience. I learned pretty quickly that being told I was free of constraints did not mean I was not imposing my own unconscious limits. Elliott had a playful way of getting me to question what I was doing and discovering new things without ever making it seem like work. Right around that time, composer-trombonist, James Fulkerson gave a concert at Bates. He played the Berio Sequenza, which I found amazing and he mentioned a composer I had not yet encountered named Mario Davidovsky. Finally, he announced a piece by John Cage in which he, “…might or might not project images.” The performance that followed involved projecting especially uninteresting photographs of Walden Pond and no sound whatsoever (maybe some reader can let me know which piece that would have been). I had just recently discovered and fallen in love with the Cage prepared piano pieces, and this “performance” made no sense to me. I arrived for my lesson with Elliott the next day angry and confused and told him how disturbed I was. Elliott pulled at his goatee and said, “I think Cage would find that a legitimate response”. It totally interrupted my thought pattern, was my first real encounter with Cage and his view of the world, and led us into an inspiring conversation that lasted the full hour.

Elliott and Eric, Freeport, Maine 2009

Elliott was the right first teacher for me. My musical chops were limited, but he made it very clear it didn’t matter. Once, I confessed to him very passionately that I was having trouble developing my ear to the point where I could hear the music I was reading in a score without the aid of an instrument. He told me that this was a useful but very specific set of skills and advised me not to get hung up about it. I would be better off continuing to practice and enjoying the many different musical experiences I was having and, with patience and time, it would all work out as long as I kept at it. This kind of message about persistence at that critical juncture in my life made a huge difference. When I interviewed Harold Shapero, not so many years ago, I was reminded of my conversation with Elliott. I asked Harold why, after great initial success, he had stopped composing for so many years. There was an apocryphal story floating around that when Harold heard that Stravinsky had started composing serial music, he tore up their letters and stopped composing. I already knew that was nonsense, but I was then at a difficult point myself and wondered what the real story was. “I lost the courage”, Harold told me as he ushered me into the kitchen and offered me a small can of fruit juice. We sipped as he stared wistfully out the window. “Your music is special – better than you think”, he said. “Don’t lose courage”.

Eric, Harold, Gunther Schuller 2005